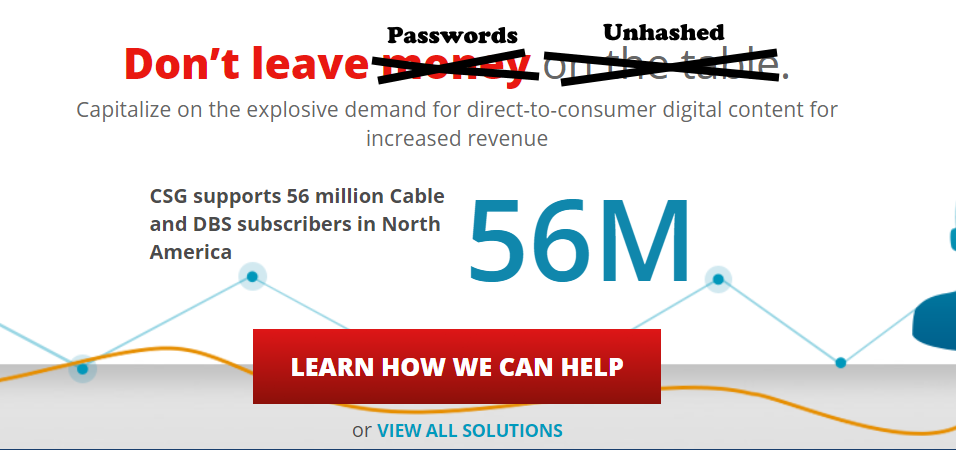

Over the last few months, I’ve tried to reach someone at my ISP about concerns I have regarding password storage practices. Namely, that they store them in a form that makes them vulnerable to being exposed in plain text in the case of a data breach. After some initial research, I discovered that the issue is actually a with a vendor called CSG International and that the passwords of 56 million user accounts are currently stored improperly.

What’s the Problem?

When I signed up for an account with my local ISP I was looking forward to a smaller, more regional provider that was an alternative to Comcast. But my concerns with them quickly started when I went to create an online account through their customer portal. The first red flag was that they disabled pasting in password fields during the account creation process. Other folks have written about this before and why it’s such a bad idea. Essentially, it prevents people from using password managers to securely create and store passwords that are unique from any other service they use. Disabling paste on sign up forms means that users are more likely to use the same password as another service they already use because it is easier to remember.

Now, this alone is enough to make me complain to my ISP on Twitter. But I went ahead and completed the signup process by stubbornly hand-typing in my 25-character randomized password that I stored in a password manager. Fortunately, they only prevent pasting in the sign-up process and I could paste my password while signing in.

I thought that this would be the end of it. I would basically set up an auto-pay for my account and never think about internet again unless the service went out or I had to move.

However, after creating my account I received a “protected PDF” via email. The email instructed me to use the same password I had provided during signup to access the PDF. Now, this initially might not seem like a big deal to some folks.

“So what? They sent you a more secure statement by adding PDF protection. Great for them!”

Unfortunately, the fact that they were able to add password protection to the PDF with that same password indicates to me they have some poor security practices when it comes to passwords. Confused? Let me explain.

When a responsible developer asks you to set a password on their website they need to take some precautions. This is because passwords are exceptionally sensitive information - they allow you to access some of the most intimate details of people’s lives.

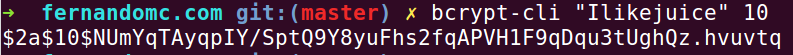

Because of this, developers don’t even want to store your passwords at all! A competent developer will, at a minimum, take the password you provide and “hash” it - or put it through a one-way procedure that consistently produces the same output. As an example, the password “Ilikejuice” might go through a hashing algorithm and turn into something like $2a$10$NUmYqTAyqpIY/SptQ9Y8yuFhs2fqAPVH1F9qDqu3tUghQz.hvuvtq.

These hashing algorithms use some clever math and programming to make this process non-reversible but consistently reproducible. In other words:

- I can’t feasibly take

$2a$10$NUmYqTAyqpIY/SptQ9Y8yuFhs2fqAPVH1F9qDqu3tUghQz.hvuvtqand turn it back into “Ilikejuice” - I can guarantee that “Ilikejuice” will always have a hash of “$2a$10$NUmYqTAyqpIY/SptQ9Y8yuFhs2fqAPVH1F9qDqu3tUghQz.hvuvtq”

This allows the developer to do two things:

- Never store your actual password anywhere

- Store and use the result of the hash to verify you’ve entered the correct password

Now, this sounds kinda complicated. But guess what, here’s one way you could do this with a single line of code:

Now, there are other precautions like adding a ‘salt’ or using many iterations of the hashing algorithm and also using a strong hashing algorithm. But hashing is one of the most basic precautions. Unfortunately, the vendor that my internet service provider selected doesn’t use this basic security step.

Ok. Ok. I’ll slow down here. You might be asking one of two questions now.

- What the heck does this guy know compared to an ISP?

- Or maybe I convinced you on the best practices and you’re asking how I know they aren’t doing this.

The best help I can give you on the first part is to point you to experts and government agencies who will tell you the same thing.

As for how I know they’re not taking these precautions? Well, two reasons:

The first reason is that they used my password to add PDF protection. The only way they could have done this is by actually having my password stored in their systems. It is not possible to use a password hash to protect a PDF in this way.

Second, my ISP told me . They’re actually pretty up-front with the fact that they store my password not hashed (the industry standard practice) but encrypted.

“What’s the big deal, Fernando? ‘Encrypted’ Sounds pretty safe to me!"

Sure, encryption is a great security tool to use - in the right scenarios it helps protect a variety of data. Unfortunately, the ‘encrypt’ in the ‘encrypted passwords’ translates to ‘you can see what this says if you have the right key’. Now for information that needs to be viewed in its original form like social security numbers, financial records and health information, encryption is great. This is because you can’t hash it - the data itself needs to be viewed and used in a way that is usable and $2a$10$NUmYqTAyqpIY/SptQ9Y8yuFhs2fqAPVH1F9qDqu3tUghQz.hvuvtq looks as much like your social security number as it does mine.

Passwords are different. Passwords should only ever be stored as a hash. Every time that there is a password data breach it is a big deal. It means that all the people who didn’t use a unique enough password are at risk of having their other accounts breached.

So how many people’s passwords are stored incorrectly?

Initially, I thought this was just a mistake made by my ISP. I brought this up with their security team and they told me that they were working with a vendor that managed their user accounts for them. But, citing confidentiality, they wouldn’t tell me the name of the vendor.

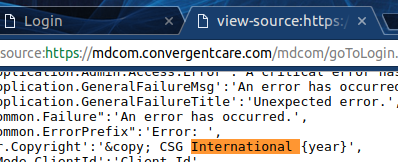

Fortunately, it wasn’t hard to find out. I started by looking at my ISP’s billing portal itself. The base domain of convergentcare.com pointed towards CSGI. I also reviewed the code of the convergentcare.com billing portal and a few other ISP billing portals with the same root domain and I found code like this in them:

Copyright in the code pointing to CSGI on multiple ISP login portals strongly indicates that CSGI is the system vendor. After discussions with my ISP it sounds like the vendor (who I am assuming from my investigation is CSGI) is aware of the issue and making steps towards resolving it. Still feeling unsettled, I decided to call several CSGI employees for comment.

After describing the problem in several voicemails I spoke on the phone twice with Joseph Wilson, Director of Information Security at CSG International. He said that “We [at CSGI] take these matters seriously and will continue to improve our products”. While I do appreciate Joseph speaking with me about my concerns, I was unable to get a commitment that this specific issue was recognized or changes were in active development. I was also unable to determine if any of the 56 million users touted in marketing materials have their credentials stored correctly. Joseph cited client confidentiality agreements that prevented him from discussing the matter in significant detail.

Not only are unhashed passwords a liability for users, they pose a serious data liability for the companies that store them in the event of a breach. For both these reasons I hope that CSGI will prioritize these changes to their software and systems and take proper precautions with the data of the 56 million user accounts they manage for their customers.